Art That AI Can’t Touch

Why no algorithm can recreate the sweet, slow magic of heritage passed down by hand.

I was mad. Furious, even. I don’t know what the right word is, but the moment I saw people turning their selfies into Ghibli-style portraits using AI, left, right, and centre, I lost it.

Don’t get me wrong, I get it. AI is a symbol of progress, and yeah, it’s useful in many ways. But does it have to be used for everything?

But then… something happened.

Mom arrived with a snack, not just any snack, her specially made Malpua. And OH MY GOD, it was divine. The perfect level of sweetness, crispy edges, that soft middle; it’s my favouritest snack!

Or maybe not entirely. Because yeah, I’m still a bit mad. But as I sat there munching on those malpuas, I started thinking that: There’s no AI that can recreate this.

No one, no one, can make sweets like my mom. (Well, except dida, my maternal grandma. She was even better.)

Usually, malpuas are reserved for Makar Sankranti. That’s also when Mom goes all out making different types of pithe-puli, traditional sweets made with rice flour and jaggery. But this batch came out of season. She had leftover jaggery and coconut, and just decided to whip up this surprise for me.

And here’s the thing: AI might be able to draw you something in minutes or give you a super-quick recipe or even make you one using the AI cooking vessels. But what can it never, ever replicate?

The love.

The patience.

The tradition passed down from hand to hand, heart to heart.

So, here’s a little collection of my favorite handmade art, crafted with the kind of soul no algorithm can touch. No AI prompt can come close to this kind of legacy.

1. Nakshi Pithe & Sandesh Moulds

Like I mentioned, every year during Makar Sankranti, without fail, Mom makes at least 7–8 types of pithe-puli. All because I’m obsessed. Like, truly, deranged-level obsessed.

But my dida? Legend. She made over 30 types when she was still with us.

Me? I struggle to make one that even tastes remotely like Mom’s. The ratio is embarrassing.

I’ve tried buying from shops when I stayed away from home, many winters, many trials, but like I said, this is a craft. A serious one. It takes years. Patience. A quiet kind of discipline that I clearly don’t have yet.

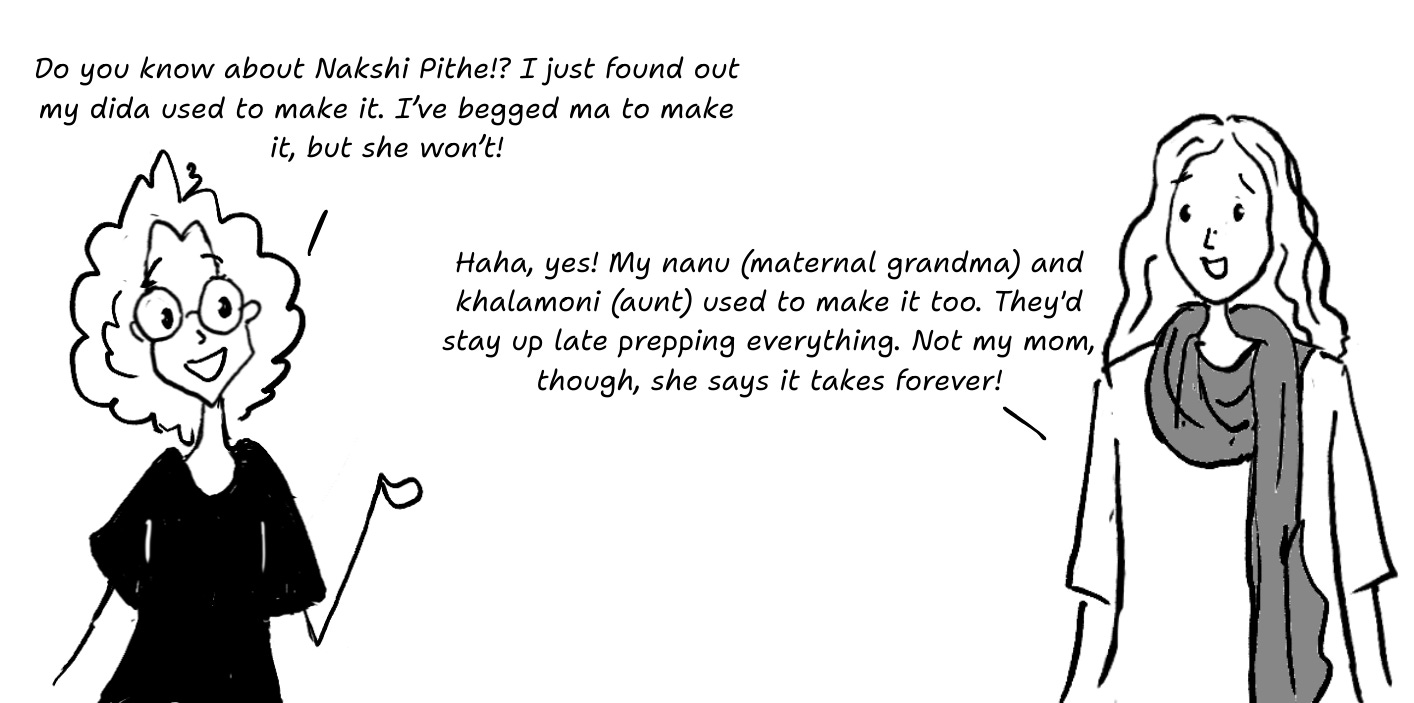

There’s one kind I’ve only heard about from Mom: Nakshi Pithe (we Bengalis call it Nokshi). ‘Nakshi’ means designs, so they’re basically designed pithe. I’ve never seen her make it, not even once. She just laughs and says, “Hehe, my mom (your dida) used to make the most beautiful Nakshi pithe. I can’t. Too much work.”

Like most pithe, it’s made of rice flour, with intricate designs carved into it. Like actual edible art. It’s so pretty, it feels wrong to eat it.

And since pithe-puli is a big part of Bangladeshi heritage, I often end up chatting about it with my friend from across the border, Nishat.

Turns out, they have pithe-puli festivals in winter with over 100 types of pithe. ONE. HUNDRED.

Naturally, I lost my mind and texted her.

And then she shared this story, and we don’t know if it’s true, but honestly? We want it to be:

Back in the British era, most girls weren’t allowed to study or make art. But they used to do floor art, alpona, using rice flour. Inspired by that, a girl from Narsingdi, near the Meghna River, started using boiled rice dough to shape flatcakes and decorated them with intricate designs.

Women were stunned. Initially, they dried those, but soon discovered that they taste amazing after frying them in oil and dunking them in jaggery syrup. The taste was a hit, and the recipe spread. Eventually, women began selling them in local markets.

Which reminds me, that’s how we make Sandesh (another traditional Bengali sweet) too. While I don’t usually like sweets, I drool over the ones made in winter because they’re made with fresh date palm jaggery

Sandesh moulds in Bengal are a whole craft of their own. Traditionally carved from segun(teak) wood or even stone, they’re passed down through generations.

My mom had a few made of stone that belonged to dida, until my aunt sweet-talked her into giving them to her, saying she wanted to make sweets for her jamai (son-in-law).

Because just like pithe, Sandesh is often made when the son-in-law visits or after a wedding, to honour the jamai.

The art of hand-carving these moulds is slowly fading away. The demand is low, raw materials are expensive, and it’s heartbreaking to see this delicate tradition kinda vanish.

If you're interested, you can check out this YouTube tutorial to learn how to make Nakshi Pithe, or simply watch the process of creating different designs. For Sandesh moulds, you can also check this video to see the full process (there are no subtitles, unfortunately).

2. Goyna Bori: Edible Jewellery

Bori are sun-dried lentil dumplings used in traditional Bengali dishes like Shukto (a traditional Bengali vegetable dish), vegetable curry, fish curry, and potato bori curry. They’re made from a paste of lentils, usually urad dal (black lentils), but sometimes also masoor, moong, or even matar dal.

Now, there’s a special type of bori called Goyna Bori. And no, it’s not your average bori, it literally means ‘jewellery bori.’

Because they’re shaped like jewellery. Yes, one of the finest forms of edible art.

Women first take a shower and change into fresh clothes before making boris, because it’s a sacred ritual. They start by grinding soaked urad dal using the good ol’ sheel nora (the traditional flat stone mortar and pestle).

The batter is then whisked by hand until it turns silky-smooth. Then comes the main act: it’s gently piped, one beautiful piece at a time, over an ultra-thin layer of poppy seeds into these gorgeous, intricate designs.

Fun fact: Before the British era, Goyna Bori didn’t involve poppy seeds at all. It was just piped over an oiled banana leaf. But when the British made Bengal grow poppy as a cash crop, people adapted, and thus, Goyna Bori got its new artistic poppy-seed twist.

The designs include flowers, leaves, elephants, butterflies, fish, shells, lotuses, peacocks, and many more. Most of these bori beauties come from the Midnapore district, and I honestly need to visit just to eat a proper one.

They can be eaten as a snack or paired with rice and dal. Honestly though, they’re crispy and light enough to munch on solo too. It’s also traditionally gifted in Bengali weddings, wishing the couple a sweet, prosperous life.

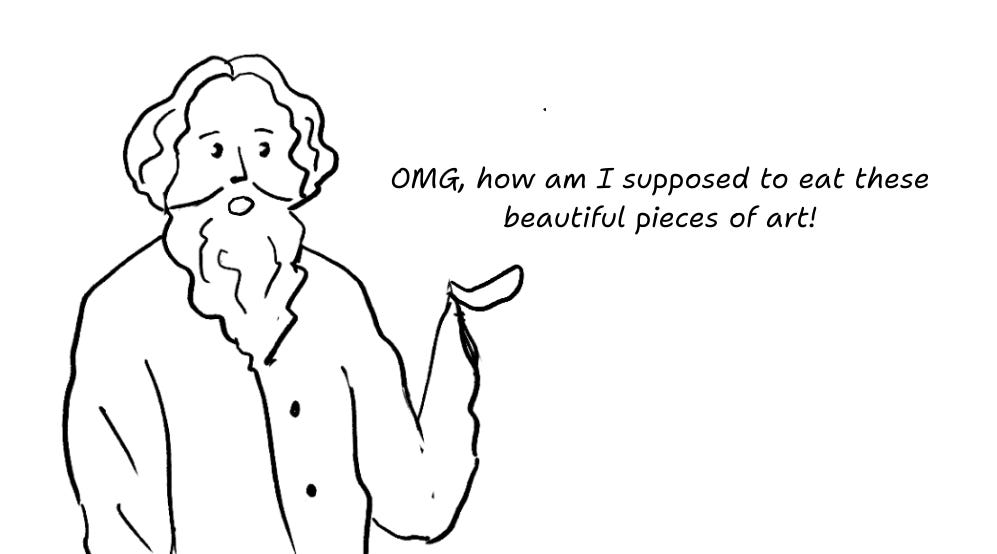

Interestingly, even Rabindranath Tagore once received Goyna Bori from a student, made by her mom and grandmother. He was so impressed, he refused to eat it.

He literally said it would be like destroying art. He had it photographed and displayed at Kala Bhavan Gallery. Iconic.

Just like Nakshi Pithe from Bangladesh, Goyna Bori too is something very few can make. It’s not passed down much these days, and yeah, it’s time-consuming, intricate, and largely a gendered practice.

You might see regular boris sold in supermarkets now, in plastic packets and all, but Goyna Bori is limited to a few communities in Midnapore.

Watch Chef Ranveer Brar explain how Goyna Bori is made in this video.

3. Alpona: Floor Art of Bengal

Most people know what floor art is, be it kolam in Tamil Nadu or rangoli in other parts of India.

Well, for us Bengalis, it’s called Alpona. And no surprises here, it's one of my absolute favourites.

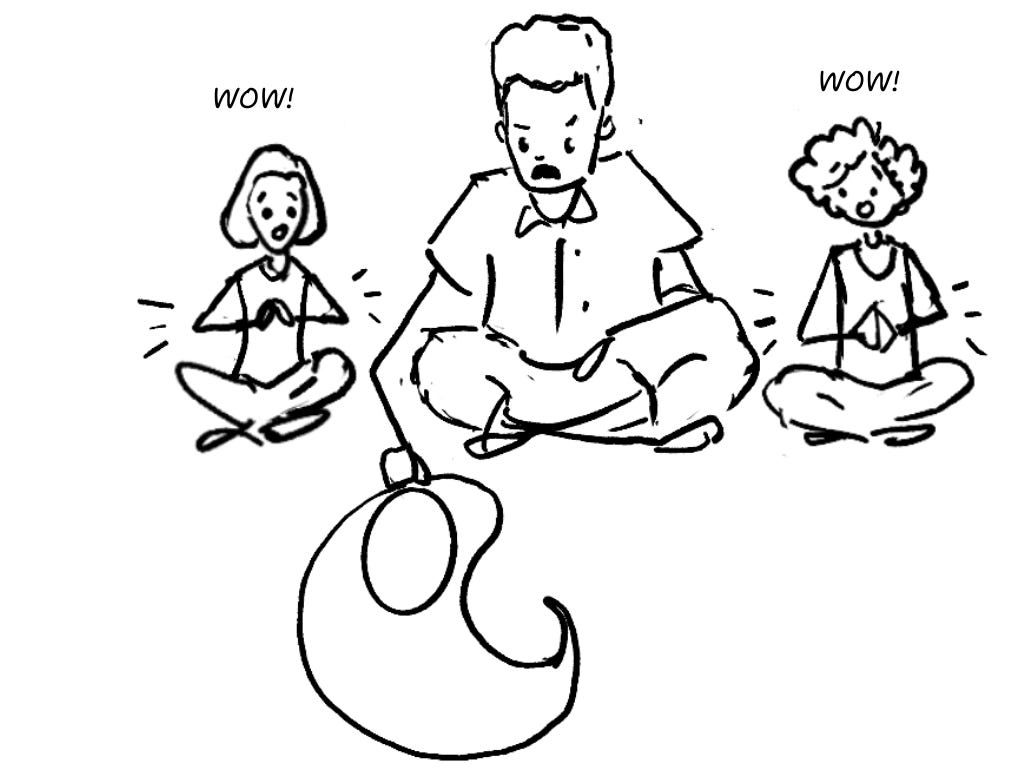

Come Durga Puja, you’ll see entire roads and platforms transformed into massive alpona canvases, especially around the space where the idol will be placed. Some localities even hold alpona competitions!

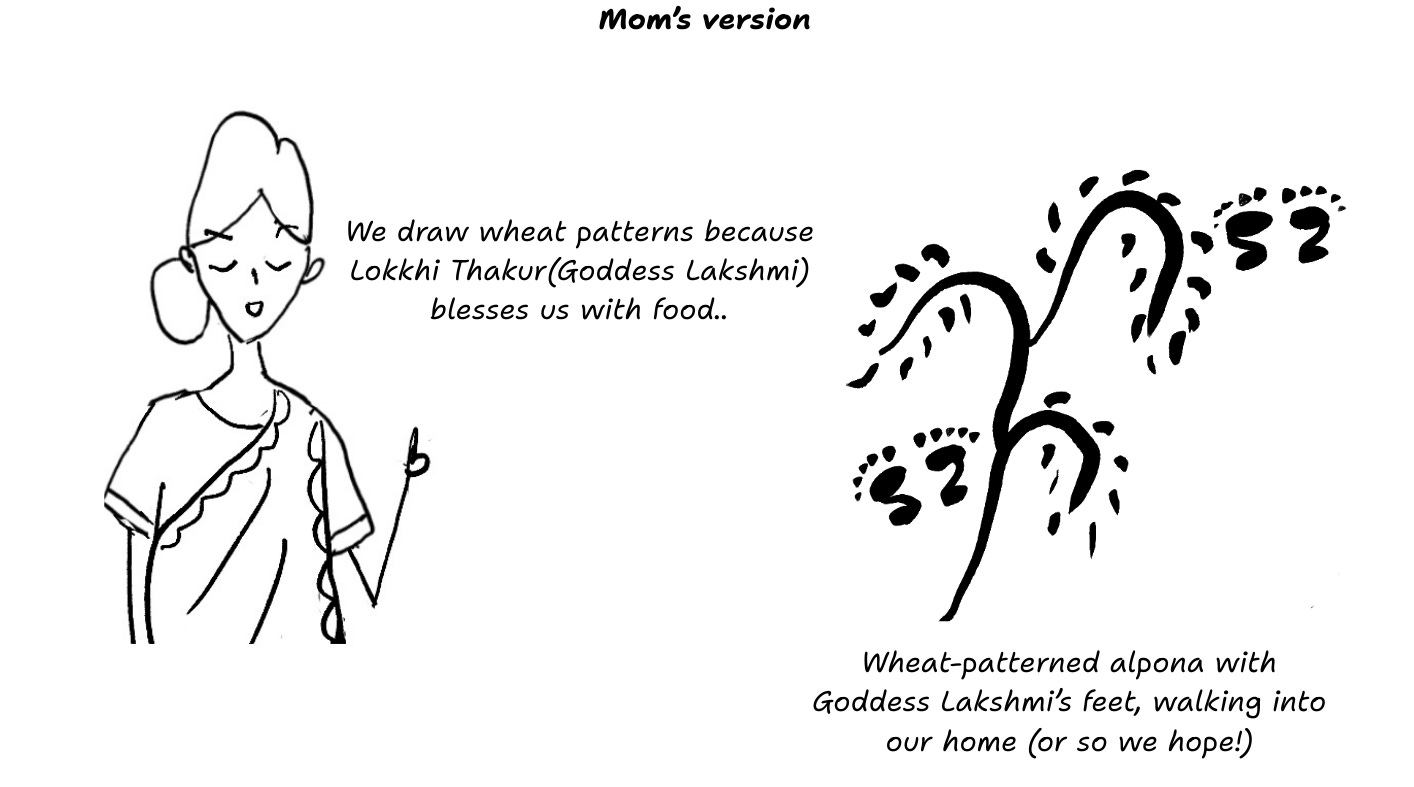

Traditionally, the base used was clay or mud mixed with cow dung (yes, earthy and sacred). The paint? A rice paste made by grinding atop chal (refined rice). Women would use their fingers to draw intricate patterns with this slurry, no brushes, no stencils, just maybe a piece of cotton cloth.

While the base colour is white, sometimes they’d add turmeric or red clay for a dash of yellow or vermilion. At home, and in most modern buildings, we use clay mixed with ground atop chal.

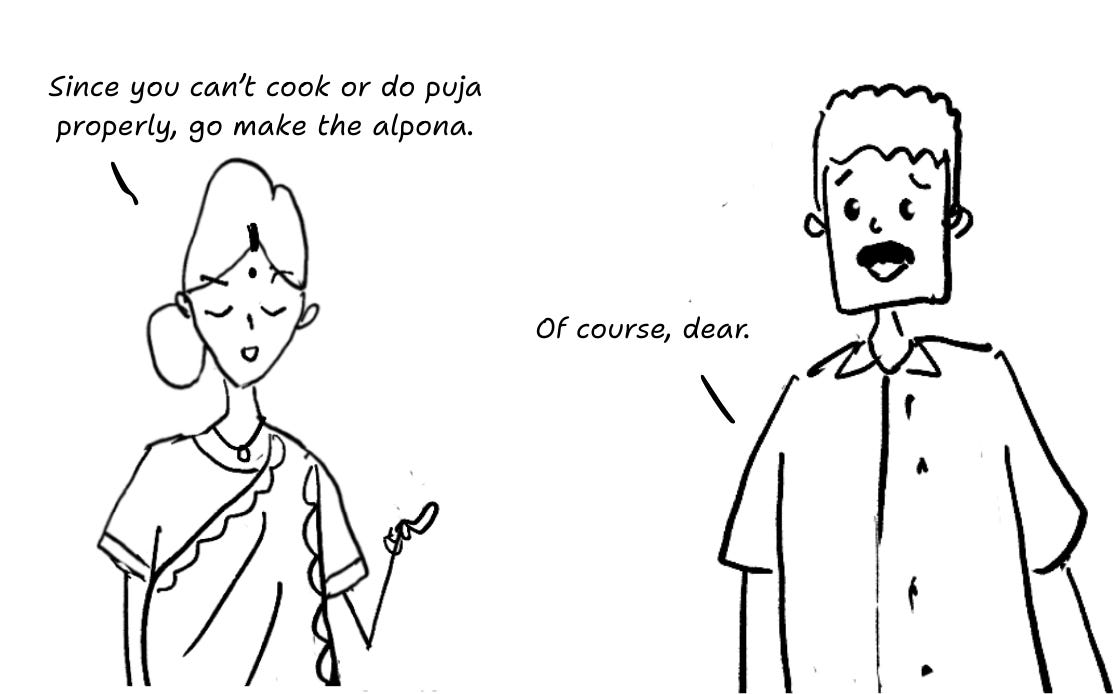

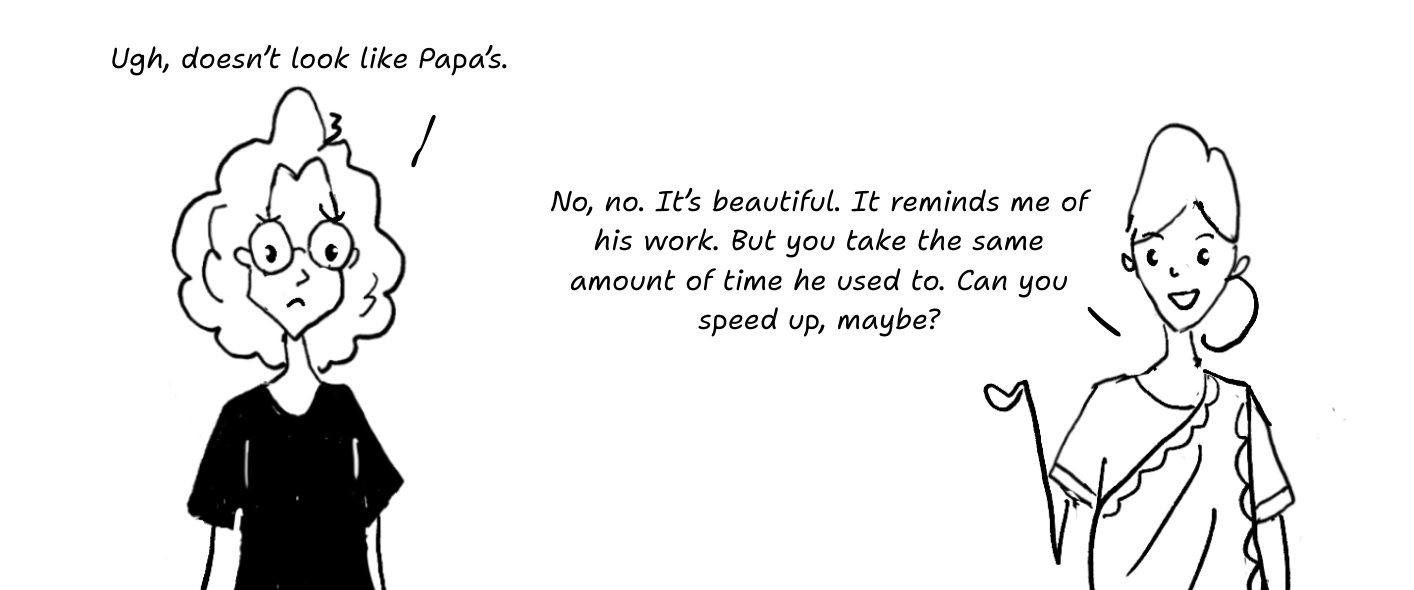

I have this fond memory of Papa making alpona on the floor during Lakshmi Puja.

We used to sit on the floor, watching him. No YouTube tutorials, no chalk outlines, just calm confidence in each swirl.

People came over in the evening, gasped at the artwork, complimented him, and my sister and I beamed like it was our achievement too.

Too bad we didn’t have smartphones then. I have zero photos of his stunning work.

After Papa passed, no one made alponas for years.

Then one year during Lakshmi Puja, out of nowhere, I felt like trying. Just a small experiment to see if I could remember the designs Papa made. I couldn’t remember all his patterns, but somehow I ended up making a giant alpona on the floor with a brush, because I can’t do the finger way. Nope.

The History

Alpona comes from the Sanskrit word ‘Alimpana’, meaning to plaster or coat. It was (and still is) largely done by women, especially in rural Bengal, often as part of Broto (ritual fasting) for wish fulfillment.

Each alpona had a purpose. During a drought, the design would include motifs of water, clouds, and hopeful verses. If they wished for a good harvest, they'd paint patterns of ripe grains, granaries, or baskets of rice.

And since the paint was edible rice flour, ants, birds, and little critters could eat it. So yes, the art was beautiful, meaningful, and biodegradable.

Originally, people even painted their mud house walls with alpona. Some remote villages still do; I’ve spotted some in Shantiniketan. Also, some people believe alpona wards off the evil eye. You look at something so beautiful, and all your negativity just melts away.

Even Rabindranath Tagore loved alpona so much, he made sure it became part of Shantiniketan’s curriculum.

I learned from this blog that many artists, including my favourites Jamini Roy and Nandalal Bose, took inspiration from alpona and developed their own styles from this traditional floor art.

Somehow, I ended up writing mostly about art forms that were originally started by women. And honestly? I’m in a much better mood now. Turns out, ranting about things AI can’t replace is a great way to refill your serotonin tank.

To quote Rabindranath Tagore:

“Art awakens a sense of real by establishing an intimate relationship between our inner being and the universe at large, bringing us a consciousness of deep joy.”

So, this joy doesn’t come from AI art. Really. And it’s not just art that AI can’t replace, it’s all the little joys too.

Like maa’s handmade sweets that taste like home. Or the joy of finding a shared memory with someone across a border. Or sitting with papa as he made alponas with his fingers, while we just watched, mesmerised. There’s no code that can recreate that feeling.

Sure, AI can pop out a flawless artwork in seconds. But I’ll still say, grab that pencil. Draw that silly stick figure. Try copying a design you saw in a book. You might not be a pro (yet), but did you feel that spark of joy while doing it?

That joy? That’s the real art. That’s what stays.

Which traditional craft or art from your roots do you treasure the most?

Special mention: Thank you sooo much, Nishat Noor, my dear friend from Bangladesh, for helping me write the section on Nakshi Pithe!

Pitha, Sandesh er bepare pore oi sob khete ische korteche ekhon. Pitha, Sandesh, Aalpona aar oi sob related history sob miliye khub valo likhecho. Thanks a lot Bandhobi :)